This interview was conducted via correspondence between Niki Korth and Marc Weidenbaum, a San Francisco-based writer, artist, educator, and facilitator who works in sound, media, technology, and community building. The topic of our conversation is the work Sonic Frame, which Weidenbaum was invited to produce for the San Jose Museum of Art’s Momentum exhibition (2 October – 22 February 2015). For Momentum, which marks the museum’s 45th anniversary, the SJMA invited local artists to create a new work in response to a work from the museum’s permanent collection that would be on display as part of the exhibition.

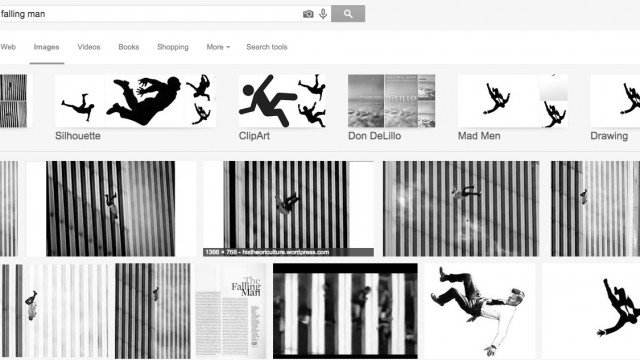

Sonic Frame is a ¨response¨ to the silent video work Untitled #8, 2004 by Josh Azzarella, which depicts a single, floating, abstract form, seemingly frozen in movement at the center of the frame. Upon reading the text on the wall, one learns that this form is that of an unidentified human figure, caught in his or her downward flight from one of the windows of the World Trade Center on September 11th, 2001.

But what happens if one does not read the text on the wall, what do they see in this image? What do they hear in its silence? What might a collective response sound like, and how is it altered through an awareness of the subject matter?

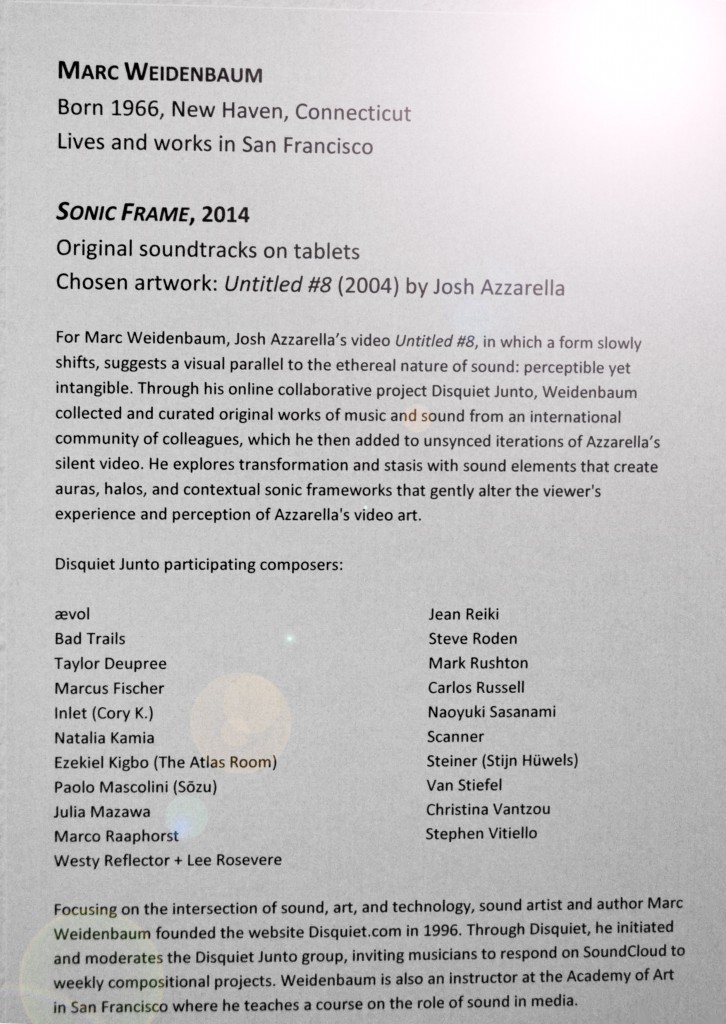

Fueled by these questions, the following digital conversation unfolded with Weidenbaum regarding the two works in question, and the 21 different scores from composers around the world that were produced to fill the silence of the frame. The musicians involved in Sonic Frame are Taylor Deupree, Van Stiefel, Natalia Kamia, Naoyuki Sasanami, Carlos Russell, Mark Rushton, Paolo Mascolini (Sōzu), Stephen Vitiello, Steve Roden, ævol, Marcus Fischer, Julia Mazawa, the duo of Westy Reflector and Lee Rosevere, Ezekiel Kigbo (The Atlas Room), Steiner (Stijn Hüwels), Christina Vantzou, Scanner, Inlet (Cory K.), Jean Reiki, Marco Raaphorst, and Bad Trails. Those 21 scores were selected from around 80 total, the majority of which were developed as part of a multi-year and ongoing online community of weekly experimental music projects that Weidenbaum founded and moderates. That music community is named the Disquiet Junto.

Q: The SJMA describes the Momentum exhibition as one that ¨disrupts the status quo¨ by inviting artists to ¨intervene¨ on the works from their permanent collection that are on display by responding to them through the creation of new works. Do you consider your work to function as a disruption, in this context? What do you see as the function of disruptions and interventions within art practice more generally, in particular as they pertain to sound?

A: I’m personally a bit hesitant about the specific word “disrupt” because of its current broad use, perhaps its overuse, as an adopted term of tech jargon. Even in tech jargon it’s a meaningful and useful term, but for every useful employment there are dozens that are less than informed, more received, less considered. But more generally, yeah, certainly: this work, like the other work in the Momentum exhibit, was generated as an act of disruption, as the word was specifically employed by the fine folks at the San Jose Museum of Art. I think the museum’s use of the word was a solid choice — the museum is at the heart of Silicon Valley, and this approach to the world, this upending of systems, is very much on the minds of many of the people who visit the museum, the people who drive by it every day, the people who live and work in its vicinity.

The goal of the interventions was to develop something original that influences the audience’s reception of the source work. “Intervention” is a word that the museum also employed, in addition to “disrupt,” and I personally connected a bit more to “intervention” than to “disrupt.” I like the idea of intervening between the original work and the spectator, the idea of being an “active spectator,” somewhere between the original artist and traditional spectator. I am quite engaged by the idea of appropriative musicians, those who work with pre-existing material, being what I like to call “active listeners,” and I saw this project as being something of an “active viewer” — someone who has an impression of what they view, in this case Azzarella’s video, and expresses that impression by making something in response.

I use the phrase “sound as commentary” a lot to describe this process, that there’s a non-verbal yet still sonic way to communicate ideas. The original video is silent and singular, and I worked on something that is sonorous and has myriad points of view. I think anything that reminds people that the art on the wall is the start of a process as much as the end of one is a good thing. We tend to think of art as the culmination of artistic intent, and it’s great to have an opportunity to make active and to present the idea that art builds on art, as well as the fact that our perception of a work can be influenced in many ways by external circumstances. I think that sound is a particularly useful tool in such a scenario because there is always a sonic content for work, even work that is intended to be silent, and drawing attention to that activity can be thought-provoking, informative, disorienting.

Q: Did you select Azzarella’s Untitled #8, 2004 as the work you would respond to in this project, or was it selected for you? If you did select it, describe the process of making the selection, including details about how the encounter between you and the work took place.

A: I selected the work. When I was invited by the museum to participate, I was sent a list of work from the museum’s permanent collection that would be in the exhibit and asked to select from that list. There was a work in the museum’s collection I had in mind, Mark Hansen and Ben Rubin’s magnificent “Listening Post,” but it turned out that piece wasn’t to be part of this exhibit.

My first conscious experience of this Azzarella video was as a color screen shot in a PDF sent to me by the museum. It was one piece among several dozen works to be displayed in the eventual exhibit. The shot looked familiar, but I wasn’t sure if I’d seen it before. I’m still not 100 percent sure if I had ever seen it before they sent me the PDF. I noted from the brief accompanying description that it was a video, and sound didn’t appear to be a constituent part. I could have asked the museum at that stage of the process to display the video for me, so I could preview it, but it being 2014 I just went to the artist’s website and located it, and in addition to being taken by it, I confirmed it had no score of its own. That fulfilled a desire of mine, that I could add music to something where music didn’t previously exist. I am particularly interested when art is displayed in a museum or gallery what is and isn’t listed as being a constituent part — you know, like on the wall text alongside it. Often you’ll see a video shown in a gallery, and it’ll list details about the film, but not even mention the sound, or it’ll note the composer of the score, but not mention whether or not the music was composed specifically for the piece. If you’re interested in sound, a museum or gallery setting is often filled with half-told stories.

Q: Did you have any contact with Azzarella regarding this piece?

A: Yes, I did. We had a very long, positive and helpful — helpful for me — conversation. I received an email from him early in the production process. The museum owns the work, all the work in the Momentum exhibit, and thus has a certain freedom with it that it wouldn’t with, say, a visiting exhibit from another museum. Notifications were sent to, I believe, all the living artists who had work in the show that was going to be the subject of one or another intervention — there were ten intervention works in all. It’s quite an expansive exhibit with a lot of moving parts. The museum wasn’t, I believe, asking for the original artists’ permission, just letting them know something would be occurring.

Part of the production process for my work was engaging with a large online music community that I moderate, the Disquiet Junto, in the development of original works of music to accompany the film. When the project was underway, Azzarella apparently listened to some of the music and shot me an email saying that he felt some of it fit the video quite well, and that if I wanted to discuss his original piece, if I would find that to be of use, he was up for it. I don’t think he could have worded it any more warmly or generously. He essentially was saying that if I felt it would help, then let’s talk, but if I felt it wouldn’t, that was cool with him.

And then we had a very long conversation about his development of the original video, in which he told me an enormous amount about its conception, development, production, exhibition, and reception. The main, direct way the conversation influenced the finished work was that initially I was going to have interstitial title cards displayed between each score, but after talking with him I decided to have the video run continuously and to put the name of the composer at the bottom of the screen for a moment each time a new score began. This change was because I learned how much the continuous repetition of the work was central to his conception. I wanted to “disrupt” the original, but I didn’t want to do so in a manner that was meaninglessly, ignorantly disrespectful of it.

Q: What was your initial reaction to the subject matter in Untitled #8, 2004, given that it depicts the form of a single, unidentified person leaping from one of the collapsing towers of the World Trade Center on 9/11/2001, frozen in motion in the center of the frame? How did your feelings about the image change over the course of the composition of Sonic Frame? What was your personal experience of 9/11, in particular, your reaction to the manner in which the event was portrayed in the media?

A: I didn’t fully understand, didn’t confirm, that this was the source until well into the project. I was reared academically in the New Criticism, as an English major, where work is considered unto itself, devoid of its original context, and while I don’t really adhere to that myself — one of my great pleasures is interviewing musicians, artists, coders, which is sort of the opposite approach — I did in this case. Even before beginning to look at any of the work in that PDF overview of the exhibit, I planned to avoid learning too much about it. I wanted to respond to the work as I might in a museum setting, where you see something on a wall and, short of looking it up on your smartphone, often have little if any other information about it.

I am pretty familiar with the holdings of the San Jose Museum of Art. I am a big admirer of the museum, and when I realized that none of the few pieces I strongly associate with the museum would be in the exhibit, I wanted just to see what, among the pieces that would be in the exhibit, I had a strong, quick, positive response to. The second I saw the still frame, just one small still frame, in the PDF, it had this beauty to it, like a cold glass of water, like an open window. I had no knowledge at that moment what the source was, it was so abstract, so tiny in the initial reproduction. Then I noted the absence of sound in the original, and that absence was very welcome to me, because of my interest in the role of sound in media. I wanted to fill that void. I’m not sure my feelings changed significantly, because I’m not really sure what my feelings were. My main feeling was engagement, enthusiasm, the mix of pleasure and anxiety that accompanies such an opportunity, to work with this museum I admire, to work with these musicians I admire, to perhaps give their work a broader and different listenership than it might have otherwise.

As for my personal experience of 9/11, like many people, I saw it reported on television. I lived in New Orleans at the time, and there was a TV at the foot of the bed, which every morning, quite early, was tuned to the news. It was a clear beautiful day in New Orleans, just as it was in New York City, and suddenly it happened. That’s a pretty huge question about how it was portrayed in the media, and I’m not sure I’m really equipped to give a useful answer. It was chaos. That’s my impression: chaos. When horrible things happen, the first thought that usually occurs to me is, “Hug your loved ones.”

Q: Are you familiar with Hakim Bey’s Divining Violence, where he discusses the idea that art can have the same magical potency as a terrorist act, but toward life instead of death?

In the text, he writes: “Terrorism has a lot in common with magic. Of course real people suffer in terrorist events – but the telos, the ultimate end, of terrorism is usually not the actual victims but the image of the victims, which will cause fear in others and force them to act or not act in certain ways. A murdered czar may be more useful here than a dead bystander, but ultimately any death will suffice. In ritual black magic there is also a victim. You may argue that magic doesn’t work, but that’s not the issue. In both terrorism and magic, an image is produced onto a field of (un)consciousness and used to manipulate it to bring about real change in the world. The process itself need not reach anyone’s full consciousness (not even the magician’s) in order to succeed statistically.”

Does this quotation resonate with you in the context of Untitled #8, 2004 and Sonic Frame, or your work more broadly?

A: I am mostly aware of Bey because he worked with the musician Bill Laswell, whom I admire quite a bit. Bey’s focus on “magic” is a bit beyond my own skeptical optimist take on the world, but I can clearly see how what Bey says connects to essential threads in the writing of Don DeLillo, like in his novels Mao II and Libra and Cosmopolis, which are concerned with various countenances of terror, not to mention the secular-spiritual effect of the “airborne toxic event” in White Noise, the existential hot zone that results. I think that what Bey calls “magic” would, in DeLillo’s work, surface as a network effect. What Bey describes as being short of “full consciousness” would, in DeLillo’s more rationalist — un-magical — literary scenarios be a kind of ambient awareness, a systemic sensation. DeLillo’s writings about systems definitely inform my experience of and attention to bureaucracies, which I’m fascinated by, and thus my enjoyment of creating and moderating the “network” that is the Disquiet Junto community.

Q: What do you recollect about what Azzarella told you regarding the conception, development, production, exhibition, and reception of Untitled #8, 2004? Especially as they relate to the central importance of the video being played in a continuous loop?

A: We had such a good, long talk, and there was so much he shared. He confirmed that it was, indeed, footage from 9/11, the same image that DeLillo, among others, described as the “Falling Man.” I had had an idea to ask folks to use text from DeLillo as source material, but when we had such a sizable response to the first Junto assignment, it wasn’t remotely necessary, or even useful, to create any additional prompts.

Azzarella mentioned when we spoke that when he first created the work he was told, I believe in graduate school, that this video would never be subsequently shown because of the material in it. But of course time passes. I grew up watching Hogan’s Heroes and M.A.S.H., which were television situation comedies about World War II and the Korean War. There’s nothing inherently funny about Azzarella’s work or the work we did in response to it. I’m just noting that at some point, we as a culture process what was once tumultuous and we get enough distance from it that, through art and narrative, storytelling and humor, reworkings and new vantages, we address it in ways that would have been difficult to fathom at the time of the original occurrence — or perhaps more to this specific point, we connect, for example, back to the black comedy that was only really possible in the midst of the events.

Anyhow, when Azzarella and I talked, he described the technical effort to adjust the original video material so the figure is always facing up, and the decision to go without any sound — apparently he usually uses sound in his work, so this was an anomaly. And he talked about the desire that the video loop, which is two and a half minutes long, be taken to the extreme that, when possible, the piece is simply turned on when the exhibit begins and turned off when it’s over, whether that’s a day or a week or months later. Of course, I don’t think that’s entirely possible always, because the repeated image will just destroy — be burned into — the screen after some time. Maybe that’s what he was after, I suppose, though he didn’t suggest it, let alone say it, and given how detailed our discussion was, I think it would have come up.

Q: What are your thoughts on the function of scarcity as well as sharing in the context of art, in particular, sound and moving image art that is rendered digitally? For example, the fact that Untitled #8, 2004 was available to be viewed freely on Azzarella’s website, and yet the DVD of it is property of the SFMA, and they gave you a specific request to pass on to Disquiet Junto participants that they should not post online any synced videos with Azzarella’s piece and their compositions?

By owning it the museum acquires the power to determine the conditions in which it may be scored (and these scored versions shared). As an artist working in ¨intangible¨ media, and also a proponent of Creative Commons licensing and sharing culture, how do these ideas resonate with you? Do you have any tension with or between them?

A: I think the Creative Commons is great because it allows people a simple, straightforward, “turnkey” way to open the floodgates to new forms of distribution and, should they choose, collaboration, specifically the asynchronous, semi-witting collaboration we call “derivative works.” I struggle for an alternate to the word “derivative” because I think it is tonally at cross-purposes with what Creative Commons is trying to achieve, but so be it. Creative Commons exists as an amendment to, an adjustment of, a parallel path to traditional copyright. I certainly wish that more work was more freely accessible for adoption, but I don’t deny that we live in a world that is largely structured around ownership.

There is, sure, an interesting tension between the fact that the artist has it online and the museum owns one of a few official copies of it. The museum has its wishes, and I was happy to work in adherence to them. Working within constraints is at the heart of the Disquiet Junto. I’m very interested in how restraints fuel creativity. That is one of the core aspects of Oulipo, which was a big influence on the development of the Junto. That tension in Oulipo is not unlike the one you cite in regard to a museum’s possession of an infinitely reproducible item. On the one hand, Oulipo often is about adapting existing texts, about transforming them, which is to say taking possession of them, which is to say not fully respecting the concept of copyright. Yet at the same time it is about rigorous rule-based formulations, which is to say working within some sort of tidy artistic law. So on the one hand Oulipo flouts the law, and on the other hand it willfully submits itself to a kind of law — it is, in fact, defined by that submission.

Q: A majority of the scores that you selected came from responses to a prompt in your Disquiet Junto project where you invited composers to compose a score to this video, resulting in seventy different compositions. Of these, you selected 14 to be a part of Sonic Frame. How did you make these selections?

A: I had even more work to select from than I had imagined. There was one Junto project to develop original pieces to complement the film, and I think we had about 70 contributions by as many musicians, produced in just over four days. I had expected half as many, even fewer, and had prepared a second assignment to broaden the field, but the result was so rich, I felt no need to go forward with a second or third related project. For the second project I was going to be more direct, more prescriptive than with the first project. For the second project I was going to pinpoint a series of key time-coded instances in the video, and to ask the composers to emphasize those moments as transitional points in the scores they composed.

Each Junto project is different. As I respond to your questions, we’re just starting the 161st weekly such assignment, with almost 4,000 tracks by more than 500 participants, and that’s not counting all the tracks that have been removed for space requirements of individual accounts, or the participant accounts that have gone away for one reason or another. I selected the 14 Junto-produced tracks for the Sonic Frame piece based on more criteria than I am fully conscious of. I wanted variety, and I knew there would be batches of work that had a particular feel — lovely, or hallucinatory, or ecstatic — and I tried to find for each broadly defined approach some exemplary, distinct pieces.

Q: 7 of the scores were directly commissioned by you from composers associated with the Disquiet Junto. Please describe these works, their composers, and the manner in which they were commissioned (i.e., what sort of direction did you give to the composers?)

A: The seven scores that were directly commissioned were the result of the same simple assignment that the Junto members worked from: to create an original score to accompany the video. I should say that while 14 were selected from the Junto project and seven were requested separately, there is some grey area. It’s often the case when a Junto project goes up that I have certain participants in mind. I’ve met only a small percentage of Junto participants, but I have a feel for the work of many of them, and when a given project goes live — even when it’s under development — I have a sense of individuals I am hopeful will be receptive to it. On rare occasion I’ll even communicate with them, usually via Twitter, sometimes via individual email, to encourage participation. More often, though, I’ll just see if I was correct, if the project did connect with them. It’s a good internal test, or check, of my abilities as a community organizer. As well, some of the people who created original scores for Sonic Frame as the result of a direct commission had previously participated in the Junto, and I just reached out to give them another chance at it, if they hadn’t done so the first time around. Otherwise they were simply individuals whose work I admire and I very much wanted to see if they would participate. I contacted each by email. Six were initially engaged, and then just before the piece was due for completion, I happened to see Julia Mazawa perform at the San Francisco Electronic Music Festival, and I contacted her at very close to the last minute to see if she could join in, and she did, which was great, especially because it turns out she’s from the Bay area and has fond memories of visiting the San Jose Museum of Art in her youth.

Q: The scores that you collected are divided into 3 sets of 7, which all play in loops, on separate monitors. Can you describe how the different ¨sets¨ are formed, and how the pieces contained in each relate to one another?

A: Each video has its own distinct set of seven scores. The three sets of seven scores were developed to maximize variety and audience interest. Each set, in addition, was sequenced to have the greatest possible number of distinct voices — distinct flavors of sound — in rotation, and for the start and stop of the tracks to be as distinct as possible, stylistically. That is, I wanted there to be no ambiguity when a given track ended and the next began. These may be mixtapes of a sort but they aren’t “continuous” mixtapes. And each of the three sets features at least one well-known musician, in the hopes that someone passing by the work might happen to notice the name and check out the selection.

Q: Are the individual compositions available online? If so, could you provide links for them here?

A: Most of the compositions that were used can be found here on the project page for that Disquiet Junto project, which also contains the full breadth of compositions that were not included in the final Sonic Frame. The only ones not on that page are the 7 that were commissioned directly.